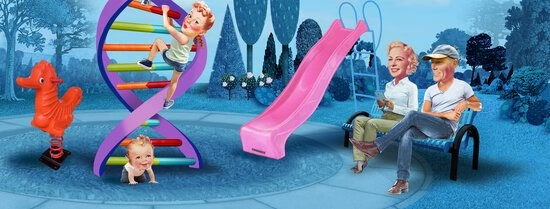

What matters more for your life outcomes: your genes (‘nature’) or your life experiences and the way you were raised (‘nurture’)? It is now widely accepted that your genes and your environment are inextricably linked and they jointly shape almost all important human life outcomes.

In our study, we investigate how nature and nurture interact to affect education. We use DNA to create a score that measures the likelihood to succeed in education – which we refer to as the genetic ‘endowment’ – while we focus on birth order as a measure of the environment, because family size puts a natural constraint on parental time investments. We first replicate a well-known fact from the literature: firstborns, on average, achieve more education than their laterborn siblings. Importantly, however, we show that this difference is significantly larger for firstborns with high genetic endowments for education compared to those with lower genetic endowments.

Identifying the 'nature' and 'nurture' effects

Estimating the influence of genetic endowments and environments is difficult. First, environments typically cluster together; e.g., higher educated parents tend to be more likely to be employed, have higher incomes and greater cultural capital, so it is unclear what may be driving the ‘environment-effect’. Second, the genetic variation that is associated with education is correlated with environments that are shaped by your parents. For example, children with higher genetic endowments have parents with higher genetic endowments (children share 50% of their genes with each parent). These higher parental endowments may have driven parents to make different life choices, such as staying in school longer and choose like-minded friends. The environment – therefore partially driven by parental genes – is then passed on to children. This also implies that it is unclear what may be driving the ‘genetic-effect’ – is it genes or the parental environment?

We know from previous studies that firstborns, on average, complete more education than their laterborn siblings, with the empirical literature highlighting the role of parental investments as the main mechanism for this ‘birth order effect’. Indeed, firstborns have undivided attention until the arrival of the second child, with evidence suggesting they receive 20-30 minutes more daily quality time compared to their younger siblings. This highlights the well-known ‘quantity-quality trade-off’: with each additional child, it is more expensive (in terms of money and time) to maintain the same investments in children. We therefore use birth order as a measure of parental investments. Another advantage of using birth order is that it is random among siblings, whereas actual parental investments (for example the time spent with each child) is confounded with other characteristics such as socio-economic status.

‘The additional parental investments associated with being firstborn are more 'effective' among siblings who randomly inherited higher genetic endowments for education’

The importance of the nature-nurture interplay for education

To look at the interplay between parental investments (associated with being firstborn) and genetic endowments, we use data on a sample of over 15,000 siblings from the UK Biobank. The use of siblings is crucial, as it removes confounding due to, for example, family socio-economic status, since this is identical between siblings. More specifically, it allows us to almost mimic a randomized experiment, where both birth order and genetic variation are randomly assigned between siblings. We find that firstborns achieve 4.5 more months of schooling than their laterborn siblings, but firstborns with a high genetic endowment achieve an additional 2 months more education compared to their laterborn siblings with the same genetic endowment.

‘Our results argue against ideas of genetic or environmental determinism’

In other words, our results are consistent with the idea that additional parental investments are more ‘effective’ among those siblings who randomly inherited higher genetic endowments for education. This is also referred to as ‘dynamic complementarity’ in the economics literature: initial skills can raise the productivity of later investments.

Our research therefore shows how genetic data can be leveraged to test economic theories. Furthermore, our results argue against ideas of genetic or environmental determinism (the belief that one’s behaviour is solely controlled by genetics or environments, respectively). Instead, genes and environment interact in important ways. Studying this interplay is crucial to better understand how nature and nurture jointly shape life outcomes.

Authors: Dilnoza Muslimova is a PhD student at the Department of Applied Economics, Erasmus School of Economics (ESE). Hans van Kippersluis is a Professor of Economics at ESE. Niels Rietveld is an Associate Professor of Economics at ESE. Stephanie von Hinke is a Professor of Economics at ESE and at the University of Bristol, and Fleur Meddens is a postdoctoral research fellow at Oxford University.

- Professor

- Associate professor

- Professor

- Doctoral student

- Doctoral student

- More information

The research discussed here is based on: Muslimova, D. et al. (2021). Dynamic complementarity in skill production: Evidence from genetic endowments and birth order. Tinbergen Institute Working Paper 2020-082/V.