Erasmus: An idealist without dogmas

Born in Rotterdam, the eminent Renaissance humanist Desiderius Erasmus (1469-1536) was to give his name to the university established in his hometown (Erasmus University Rotterdam) four centuries later.

Erasmus is an obvious choice as name-giver for our educational institution, not just because the historical Erasmus was a Rotterdam scholar of great renown, but also because he was an engaged scholar. His teachings focused on tolerance, moral integrity, social justice and non-violence, his work was always intended to have some positive societal impact, and his conviction was that the promise of a better society lay in the prospect of improving education.

A scholar as well as a sixteenth-century ‘influencer’, Erasmus wrote a lot – and what he wrote was often widely read. Fully dedicated to the project of raising his fellow Europeans to new cultural levels, Erasmus told them how to speak, how to write and how to act.

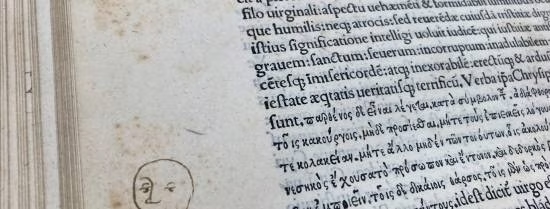

Erasmus’s ideas on education gave a central position to texts from classical and early Christian antiquity. As a humanist scholar of the bonae litterae he put much philological effort in reconstructing ancient texts from their corrupted medieval manuscript manifestations. His restored texts of Lucian, Cicero, Cyprian, Augustine, Euripides, and many others had to provide especially young readers with a thorough knowledge of the classical languages. Their content functioned as moral instructions and taught readers how to become compassionate Christians. Erasmus even approached the Bible itself in this philological way. In 1516 he presented to the world his most controversial work: a renewed edition of the texts of the New Testament.

The Primacy of Practice

In questions of religion, Erasmus was inspired by anti-ritualistic interpretations of faith and a view of religious calling as an inner state of mind rather than a matter of outer display. This deeply-felt need to focus on practical effects rather than theoretical beliefs was mirrored in Erasmus’ anti-dogmatic positions and his rejection of anything either extreme or inhumane. Erasmus’ proverbial pacifism, for instance, was not so much based on philosophical principles as on a responsiveness to the fact that in waging war, almost nothing can be won, and everything, including the essence of humanity itself, may be lost.

An educator at heart, Erasmus never failed to criticise even Popes and Kings, always avoiding to become unnecessarily personal. Committed to what he himself defined as the Philosophia Christi as his touchstone, his goals were expressed in religious as well as philosophical terms, but were always related to social and political life. Whether he dealt with manners of conduct or questions of morality, what Erasmus taught focused on questions of personal development, expressing the essentially Platonic doctrine that no-one becomes a human being simply by being born, but only by being raised and educated in the right manner. For Erasmus, civilising oneself is something for which every individual as well as every generation will have to make a continuous effort.